South African President Jacob Zuma flew into Jomo Kenyatta International Airport in Nairobi on Sunday night– and disembarked from his plane. That may not seem, on the face of it, an exceptional event. But it was. The only other South African presidents who flew into this airport, at least since the dawn of democracy, did not leave their aircraft.

On Kenyatta Day in 1997 former president Nelson Mandela arrived at the airport and officials laid out the red carpet for him. Kenyan foreign minister Kalonzo Musyoka duly went to the airport to officially greet him. But, as reported by Carlos Mureithi of the Daily Nation, Mandela did not emerge from his aircraft. Embarrassed South African officials told Kenyan officials that he was asleep after a long journey from Egypt, heading for home.

The Kenyan government was rather miffed but apparently did not complain. But then, two years later, it happened again.

Former president Thabo Mbeki also did not alight from his aircraft in Nairobi, leaving another Kenyan minister twiddling his thumbs on the red carpet below. As Robert Otanireported for IOL, Mbeki’s spokesperson emerged from the aircraft to apologise, saying the president was sleeping as he had worked until dawn that day, trying to mediate peace in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Mbeki was re-fuelling, en route to Libya for a special summit of the then Organisation of African Unity.

Relations between two key African states were evidently dormant – quite literally.

Analyst Emmanuel Kisiangani cites these two incidents as evidence that “the rapport between them continued to be poor” despite the two countries having established official diplomatic ties in 1992.

Some believe that frosty relations were a result of the African National Congress’s (ANC) belief that Kenya had been too friendly with the old apartheid government and not supportive enough of the ANC’s liberation struggle.

Professor Peter Kagwanja, Chief Executive of the Africa Policy Institute in Nairobi, partly agrees. He notes that Kenya was one of the few African countries Mandela visited soon after he was freed from prison in 1990. At a big rally, Mandela paid tribute to the Kenyan nationalists who fought colonial Britain saying they had inspired the South African liberation struggle. But, in his forthright way, Mandela then also rebuked Kenya for not honouring its own liberation heroes.

“President Daniel Moi was quite unhappy. Mandela had started stepping on the sensitive toes of tyrants of the time. I would say this was the start of the lukewarm relations with Kenya,” said Kagwanja.

He adds that Mbeki did not help by taking “a high-pitched ideological stance on Kenya”, covertly siding with former president Mwai Kibaki’s chief rival, the “pan-Africanist” Raila Odinga, whose father, Jaramogi Oginga Odinga, Kenya’s first vice-president, was said to have supported the ANC’s struggle.

“Between 2004 and 2008, South Africa’s foreign policy towards Kenya operated on this false dichotomy of the Kenyan elite as ‘pro-nationalist’ and ‘pro-apartheid’. It did not help matters that the ruling elite frustrated the efforts of South African companies such as Castle Breweries and some banks to penetrate and gain roots in the Kenyan market.”

Kenya invoked patriotism to defend protectionism, adopting the slogan: “Tusker: one nation, one beer” – and Castle lost the fight and relocated to Tanzania and Uganda. Local banks such as the Kenya Commercial Bank and the National Bank rejected overtures to sell stakes to South African investors.

“What started as a misguided ideological war took on a serious and legitimate economic angle,” said Kagwanja.

In 2008, as Kenya plunged into the bloody violence after the December 2007 elections, key members of Kibaki’s Party of National Unity suspected that people close to the ANC government were not only bankrolling Odinga but also giving him diplomatic support, he says. Consequently Kenya flatly rejected efforts by Desmond Tutu and Cyril Ramaphosa to help resolve the crisis.

Kagwanja believes that the Cold War with South Africa also shaped Kenya’s relations with its regional neighbours. South Africa favoured Tanzania as a former “frontline state” during the liberation era and a fellow-member of the Southern African Development Community. Kenya felt this was part of the reason for Dar-es-Salaam’s “cavalier attitude” towards the East African Community and so Nairobi turned more to other neighbours, especially Uganda and Rwanda.

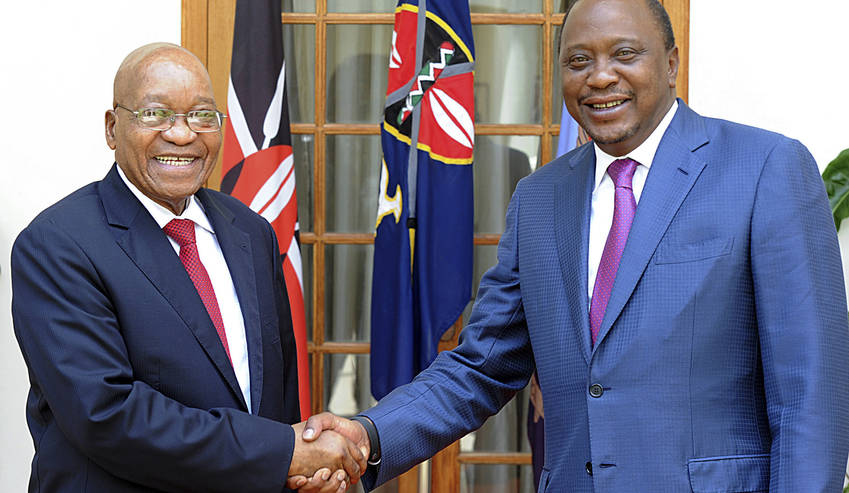

So when Zuma described his visit this week as “the beginning of a new chapter in the history of bilateral relations between South Africa and Kenya” he was expressing more than the usual diplomatic platitude.

Kagwanja attributes this resetting of relations to Zuma’s decision to avoid the “mistakes” of the Mbeki era. He cites, in particular, Zuma’s open support for Kenyatta and his deputy William Ruto in their long battle with the International Criminal Court (ICC), which charged them for crimes against humanity in allegedly orchestrating the violence after the 2007 elections.

Until 2013, South Africa was a strong backer of the ICC, and even warned Omar al-Bashir, the Sudanese President, not to set foot in South Africa in 2009 and 2010, given the risk that he would be arrested and transferred to the court. However, after Kenyatta was elected in 2013, the South African government stance seems to have shifted, with South Africajoining other African Union states in their offensive against the ICC.

Kagwanja notes that Kenyatta has also played his part in mending fences with South Africa, never missing an opportunity to visit the country.

The often-fraught economic relations between the two countries also came under the spotlight during Zuma’s visit. South Africa enjoys a huge trade surplus, exporting R8.3-billion worth of goods to Kenya and importing only R366-million in 2015. So Kenyatta’s spokesperson announced that the president would urgently appeal to Zuma to cut South Africa’s import tariffs on Kenyan products such as tea, processed meat and soda ash.

Kenyatta also appealed to Zuma to ease visa restrictions on Kenyans, including allowing them to get visas on arrival, as Kenya allows South Africans to do. The results of these entreaties are not yet quite clear. Zuma agreed, at a business forum, on the need “to soften borders to promote cooperation and intra-African trade” but was short on specifics.

The two governments did agree to scrap visas for diplomats and officials but Zuma would only say further visa relaxation would be considered. He expressed concern about criminals and others abusing more open borders.

The two governments signed six agreements in all to improve cooperation, including among police and defence forces and broadening the counterterrorism partnership to include cyber security, financing of terrorism and stemming radicalisation.

Relations, clearly, are at last on the mend across the board. Whether the price for this new entente cordiale was for Zuma to turn a blind eye to a few Kenyatta unpleasantries remains, however, a worrying suspicion. DM

Alleastafrica and Daily Maverick