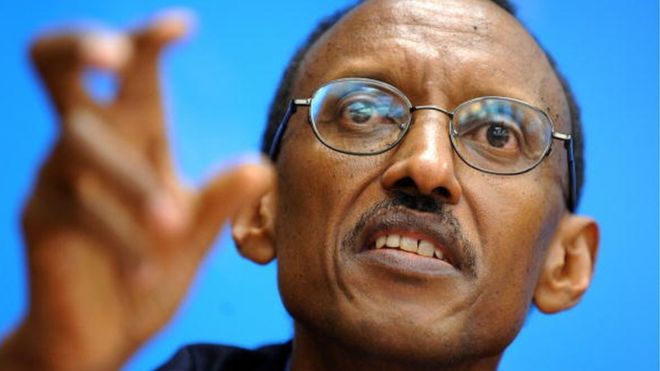

KIGALI – This is an edited transcript of an interview conducted with Paul Kagame, president of Rwanda.

Financial Times: I’m interested in how you’ve approached the monumental task of the “rebirth of a nation”. And in that context, the way the west sometimes looks at what has happened in Rwanda and looks at your own presidency, and is sometimes critical, perhaps it would also be good to hear in what way you think that Rwanda is misunderstood.

PK: In the case of the whole history of what has happened here, our involvement in it and what we did and . . . at a personal level, I wouldn’t say there was a process to prepare me as a person to deal with the situation we had to deal with at a later stage, other than the conditions we lived under. From childhood. My family fled this country in 1961 when I was four years old. I grew up in Uganda in a refugee camp, a couple of decades, and so it was when I was about 19 or 20 that I actually started getting involved with the . . . maybe I call it politics. Something to do with asking ourselves, what is this, what is this situation we are in, why and what can we do about it, and so the main activity started among the people in exile and different places, especially the region, whether it was Burundi, Tanzania, Uganda and so on.

So that’s until we came to the mid-1980s when the Rwandan Patriotic Front was formed, but there had been other attempts before that trying to organise, but concealing it because of the problems they attracted. Then later on we joined, a couple of us, [Yoweri Museveni’s National Resistance] army in Uganda when there was this armed struggle in Uganda, and that’s how we prepared ourselves.

We were not getting involved because we believed we were Ugandans or because we thought we really needed to be made Ugandans, but we participated because, one, we were being affected even as refugees. In fact, there were people who were forced out of Uganda and thrown back into Rwanda who were refugees because of the politics in Uganda at the time. Some of them even when they came back they were killed, and others survived and became refugees twice.

I’m just throwing a little bit of background where we originate from.

It is not that we developed or grew up under normal conditions. Some of it just happened, and we found ourselves under these conditions and yes, some of us didn’t accept that. Of course, many succumbed or gave up, and in fact many lost their lives because they had also lost hope, but a number of people stood up to deal with these challenges, and that’s how . . . that’s the origin of the struggle for us. In fact, when it all started in October 1990, I was at a military college in the states.

FT: Right, in Kansas.

PK: In Kansas, the US Army Command and General Staff College, and I was there as a Ugandan. So, when it came to the time when the invasion happened, October 1, that is the right time we need to do whatever it was and whatever risks it carried, but we needed to do something.

We weren’t sure how it would turn out. And, of course, as I mentioned to you, things that followed, things that happened indeed would point to the unpredictability of that kind of situation. So even when I went to the commanders of the college and told them I had to cut short my college stay, they got confused. They said, what does that have to do with you, what’s happening in Rwanda? You are a Ugandan. And I told him, I said, not exactly. For the purpose of being here I was Ugandan, but something else has happened and that now brings me out to be who I actually have been all along.

So that’s how I left. I came back. Already the overall commander had been killed the next day. Fred Rwigyema was killed. So when I arrived, I found everything in disarray.

I told him [the commander in Kansas] that something else has happened and that now brings me out to be who I actually have been all along

I literally didn’t know where to start from. Nothing had fully, if at all, prepared me for dealing with such a mess. I had no reference to anything to say this is how you do it, but we had to pick up the pieces and then find some way to start rebuilding. In fact, I remember some of the commanders . . . You will bear with me — I am going into this length of explanation to just come to the point you were asking.

I start to meet the commanders who were there, and gauge how prepared they are to deal with the next phase that was so challenging, and I remember a number of them saying, “I think we go back to Uganda and ask President Museveni . . .”. This was to give us another place where you can go and stay as refugees. So here the choices were clear. You go back and become refugees [or] continue the struggle, and the possibility was also that we will be annihilated.

So we chose the more difficult thing, which was face annihilation or be able to really reorganise and survive and then fight back. So I’m saying this because these are conditions that you have not thought about before or something we expected to be of such a magnitude, but when it happens and you are confronting it, it arms you with certain abilities or capacities, both of the heart and the mind, to confront it, especially knowing the alternative is unthinkable.

For some of us, the alternative of going back to Uganda as a defeated group and asking for another opportunity to be refugees was unthinkable. So we had to deal with this difficult path, so we tried to organise. That’s how we shifted the forces and moved them across the border, close with the border within Uganda up to the mountains.

People used to die. We used to find some of our fighters frozen to death. Yes, we barely survived — freezing and under such conditions when you even have no food, or very little, but we survived it, but it also gave us an opportunity to reorganise.

So, yes, to come now to the leadership question. I think there is a lot you learn from what has happened to you, what you have had to confront, not how many books you have read about leadership, not how peaceful the environment you have grown up in. Those difficulties, that kind of a situation I think explains the conditions you are operating under or things you face, if you have made the choice to deal with it, because during this struggle there were probably as many people who gave up as those who stood up.

FT: You had to restore discipline to an army, in your words, in disarray.

PK: Absolutely.

FT: And you had to come up with a plan, but you were also capable of improvisation. So, now as president, how much is there still of that Spartan discipline in the country, and how much can you allow some improvisation?

PK: Yes. A lot of improvisation has had to happen, right from the time . . . in fact, that’s really the essence of starting my story that way. I fought these two wars, one in Uganda and another in Rwanda. In Uganda it was a small army that started. I was one of the 27 who actually invaded the barracks called Kabamba in Uganda and so on. There were 40 but only 27 of us were armed.

The Ugandan side was a small force, [but with] big political support.

In our case, it was the reverse. The group that started the war was big, bigger than what started in Uganda, but with very small political support because Rwanda was organised in such a way that it has been in the past and on ethnic grouping, ethnic politics and then majority Hutus, minority Tutsis, the Twa and so on. So we had this capacity, military capacity. There were already between 3,000 and 4,000, and all armed.

But the political side was almost non-existent.

Not only were we referred to as a minority, and in fact later on the military arrested Tutsis in Kigali and some of them died, even at that time, but we were actually also called foreigners. On the one hand, they would associate us with a minority here who wanted to take power, but on the other, they would say, no, these are not even Rwandese, they are foreigners.

So, what this leads to eventually is a number of things. One, how do we convert, how do we turn this overwhelming political tide against us and actually turn it into our favour eventually? But we have to survive because we had this force. So in that survival game and process, either way, instils in the people saying, there is a huge task here to perform but we have no resources, so where do you start? It starts by saying, I use as little as I have so effectively to overcome the adversity. That’s already a discipline. And that even says, oh, you have so much to deal with, but you have so little in terms of means. So you make sure, if it is a dollar, you make sure that you get as much as you can from a dollar.

So, as a way of surviving and creating the outcome we want, that already is the level of this thing. So it has gone from that time of the armed struggle, even to running the government, and that’s why even in terms of, say, how we have used the foreign aid, we have always said, well, first of all, even if it would be sufficient, you are not sure it will keep coming. The next day somebody will say, no, no, I think I’m tired of these guys. So you’re always thinking ahead and saying, what if this happens? So, maybe [I’m] happy that it hasn’t happened yet, but if it were to happen, it should find me prepared.

FT: You’re speaking to an essential precariousness.

PK: Yes.

FT: You say you had by then a battle hardened group of soldiers that had suffered but were tough, but you had no political movement. Now, fast forward to today. You still have a really respected army. But here’s the difference, you’ve almost been too successful with your political movement. You’ve just been re-elected with 98.7 per cent of the vote.

PK: Yes. That is also a result of the work I mentioned to you. When we had the thirst to survive and had a big political tide against us to deal with, the work started there. In fact, the political support we had united behind us was outside of the country and very little inside. So, when all this was over in 1994, we now brought the support that was outside and multiplied support of the inside by doing political work. We were still outnumbered by far in terms of the political side, because when we survived the war between 1990 and 1994, these years were spent on trying to convince people.

I was just trying to actually link that, show you the thread that connects from that time even up to the present, how the political work we had been doing and the dynamics of the whole situation added up even to the present, where you find something close to 100 per cent saying this. It is because of this work that was done in between.

FT: Does it matter to you that some people say, please, nobody wins 98.7 per cent of the vote. It’s just not credible. Did you ever think, actually, we don’t want to win by 98.7 per cent, it’s too much? How do you answer that?

PK: How I answer that is by . . . in fact, that’s what has maybe up to this day helped us to make this progress. We live real lives on the ground. We don’t live by some theories somewhere. No, it is this thing, the daily thing we are confronted with: it determines what we do and maybe what we get in the end. This is my starting point.

The other . . . Let me give you an example, which you probably have known by now. In these elections of Kenya, right. You know that there are constituencies where you have 500,000 people more or less where Uhuru [Kenyatta] would win 99 per cent, right? Not one place, maybe two, maybe three, right? One would have said, it’s because he’s the incumbent and therefore he must have manipulated. But it also happened on Raila Odinga’s side. There are places where Raila Odinga won 98 per cent, 99 per cent. Very well, you see?

Now, the dynamics behind this are different from ours. In Kenya, it’s because of this ethnicisation. In our case, it’s completely different. It depends on this story I told you from the beginning that also has elements of the structures of our society or even the history.

Because of what happened here — and we have genocide, we have perpetrators, we have victims, survivors. What we have done to confront that, that we still have to confront even today, one, the survivors think this government has done things that give them hope for the future, that probably nobody is going to come back and kill them, right?

In Kenya, it’s because of ethnicisation. In Rwanda, it’s completely different. It depends on this story I told you from the beginning that also has elements of the structures of our society or even history

But the perpetrators also see this government as the best thing that can happen to them, for one single reason. Someone who said, “oh, but I have actually been found to have killed families of a number of people, but I’m still alive. My relatives have not been affected”. They didn’t go and say, “oh, you’re a son or you’re a father or you killed people, so you pay for it”. In other words, they feel indebted in some way.

So, normally we would face justice, but this has not happened. And where it has happened, it has happened in a manner that is really aimed at dealing with the problem, nothing beyond that.

In the previous government or governments, they even used to call it Hutu Power, but when it comes to your life and you ask one of these people: “OK, what does that mean?”. His child was not going to school. Oh, they had no access to anything. We are still dealing with that, but at least we are making a dent into it, trying to reduce poverty and so on. The only thing they knew was poverty and misery, especially if you go to these rural areas. And now their children go to school, they have health insurance coverage that covers the whole country, they have food to eat. They can now grow their own food, they don’t line up to go and pick daily rations like we found it. The World Food Programme was the one feeding these citizens of our country. No more.

Now there is stability, there’s a sense of security, there is hope.

FT: Do you think you have now successfully created a new Rwandan identity?

PK: Without a doubt.

FT: In which people now no longer think about Hutu or Tutsi?

PK: Without a doubt. There is nothing that is 100%, maybe except this vote.

FT: So you don’t need to stay in power to keep a lid on that?

PK: Absolutely. I don’t need, and I’m not there because I needed it, absolutely. This is the first point. I know it causes confusion, and that’s what I see written all over the place.

FT: I’m interested in these misunderstandings.

PK: It’s as if I had some plot, but let me tell you a bit of history as well so it is clear from fact. One, even when we had just taken over, I don’t know what story you know about it, I’m the one who refused to be president in 1994, absolutely. There is this man called [Faustin] Twagiramungu, he’s in Brussels, who was in the opposition at that time. He was part of the Arusha agreement [in 1993], he was prime minister. He came to see me. They had taken it for granted that I was going to be president [Pasteur Bizimungu was appointed president in 1994].

Then I said no, there’s nothing for granted. I’m actually not intending to be president.

FT: And the reason you gave?

PK: Well, several reasons. I first of all told the party that the highest position goes to the chairman, not me. So we agreed. We sent in the name. They said, what about you? I said, in actual fact, I don’t want to be the chairman . . . the deputy prime minister. I don’t want to be the deputy minister of defence. I will choose to be the deputy chief of staff, and I told them the reason. I said, I think I want to be close to this army that we have fought alongside. I want to remain close to our fighters, so that when things happen there is still an insurance that we can pull back and fight back and secure ourselves. That’s one.

I said, I don’t want to be president. The president will be there, will be bogged down by some other things, but look, we have millions of people across the border [Hutus in Zaire] who are still armed and have tanks, they have war weapons and they’re organising, they’re attacking us already, and I’m not going to be president [and] at the same time seek there and start fighting.

Second, I told them, you know what, let’s choose somebody who grew up here, who knows people, who knows all the aspects of this environment of Rwanda. I don’t feel I’m prepared enough. And I told them, another danger is there is this thing we still have to deal with where we were being referred to as foreigners.

So that was my reasoning. We still have security to create. Second, I’m not comfortable with my background and identity, and I said, I’m not creating a good image for these ordinary people who are still confused. They will confuse the whole thing. So I said, I need to stay out.

I’m just trying to tell you. It’s important for me. I never wanted even to become president. It’s not something I worked for, because I was not even sure for my five years in Uganda in the war, four, four and half years in Rwanda here, every single day of that time I was not sure I was going to survive to the next day.

FT: History has a funny way of repeating itself because a couple of years ago, according to what we’ve heard and been told, the party [Rwandan Patriotic Front] came to you and said, we want you to serve a third term.

PK: This is what they did.

FT: And you didn’t want to?

PK: I didn’t want to. We had a long argument. You need to understand these facts. We started it in 2012 or 2013. We had a two-year period, and because I had already had these sentiments, people saying, you know, come 2017 . . . Some people wrote letters to me. There’s a man from Rusizi [in Rwanda’s Western Province]. A local person, but a businessman. They wrote, but several of them, they wrote to me a letter and said, President, we have never had what we have in our lives [now]. It’s only because of you that the country has come together and we have these things.

And then he said, a level of trust has developed among Rwandans because of you. He said, if you go too early, I’m afraid things will fall apart.

FT: But that was my point in a sense. Is that fear justified?

PK: You can ask him. I don’t know, because I’m not the one saying that.

FT: But do you fear if you’re not there things could fall apart? Is the success that Rwanda has now dependent on you, or have things become institutionalised so that they can outlast you?

PK: That’s fine. Well, first of all, whatever it is, it is no fault of mine. If I would be accused of having created a situation where the focus is me and not anything else or anybody else . . .

FT: Well, it’s not really an accusation.

PK: No, no, no, I’m explaining. In any case, I’m not being interrogated. We’re just having a conversation. But the point I’m also coming to is these questions or arguments that seem to be obsessed with the person and not look at the situation, even from you analysts or others. I find it bizarre.

Now, you either believe it and try to find a reason . . . It doesn’t become my duty to actually defend myself and say no, no, because I’m not the one creating that condition. This is why I took the initiative and called the party in 2013 and sat with people. We spent two nights. I brought it up with them because of these messages I was receiving. I put it to them. I said, please, come 2017 we need to reach there when you have decided what you are going to do.

FT: We need a plan?

PK: This is what I told them. And I told them my thinking of what the plan should become. I told them, for instance: one, be careful. Don’t just reject change because change can also be good. I said, think about it realistically and come up with a solution, but just don’t reject change that is likely to come when 2017 comes, that you can have somebody else.

Two, I said, we need stability to continue. Three, we need progress. The country’s economy, socio-economic transformation, needs to continue. I said, so think about these, but I started with change and appealing to them not to be afraid of change, meaning I was asking them, think about it realistically and even the sustainability of what you have, as opposed to the change that maybe should happen. So this is how I directed it when I started feeling this.

I was saying to them, don’t think that when you want Kagame next after 2017 you necessarily have him. But my point was to say, try and look at those things that if they are not in place you need to put [them] in place, so that you are not afraid of this.

Now, if these people come back to you and say, we are not convinced, and people are saying, no, things can be a matter of time. We are not saying we want you forever until you drop dead. We’re only saying, give us more time.

This man Trump, he’s a product of your democracy. Sometimes the democracy you tell us to emulate, but you are here complaining about what your democracy gave you

So we are here where we are. When it was coming to the nomination time, and all along I kept pushing back, up to the last minute. Even when I was nominated, I decided not even to write a speech. I spoke from my heart for about an hour to these people and I told them. They were visitors who had come from across Africa. I told them look, I would have been here, happy, thanking you and handing over to somebody else, but you have not accepted that to happen. So I’m having to accept your nomination, and I will do under that mandate my best to serve you as I have served you in the past.

But here is a caveat. I said, this time I want you people after the seven years ahead, when we come to that point, we should not be repeating the same thing. Let’s try to fix whatever we can fix in these seven years to make sure that we are not back in the same position where you have to ask me to continue. That’s what I told them.

There is also the reality of the situation versus the obsession that Kagame has been here for too long . . .

FT: Is it not the case that what makes this particularly difficult is that you are the dominant political figure but also de facto the army is loyal to you, and you have to make sure for the country, for the national interest, something slightly has to change because nobody’s going to be able to replicate your dual role.

PK: Sure. Well, the problem we have is not even just to have somebody to duplicate my role. The problem is actually also having to prevent somebody bringing down what we have built.

It’s a good problem. It is a better problem than many we had before us. Why are you not satisfied, some journalists or some human rights activists? They have their arguments which people can pay attention to, that’s fine, which may even take a lot of marks from our situation, but having said all of that, when it comes to the choices, to the lives of Rwandans, these are the ones that override. I’m sorry. I have even told some people openly and some of these politicians . . . go and hang.

FT: Go and hang?

PK: Yes. As long as this is the choice of Rwandans, and they are happy.

FT: We should ask you about the economy, but I just have one more question, if I may, on this vein.

Westerners would tend to see this as an authoritarian society. But you may well see what you have created as a different type of democracy, one based perhaps on traditions that maybe go back hundreds of years, and one that maybe has its roots in the RPF, the camps of Uganda, the fact that this is how you came to power?

PK: Maybe let’s talk about democracy, and not western democracy, because is there something called democracy without putting the western thing? If we can do that, maybe that’s where I stand. And I look at the ingredients of democracy generally, not making it western, because making it western raises many other questions.

I’m not British, I’m not American, I’m not French, Whatever thing they practise, that is their business. I am an African, I’m Rwandese, and there must be universal principles and values that people want to identify with. I’m not here to champion western anything. There are things I like about the West, absolutely, and learn from and want to emulate. But this whole thing of measuring, you forget my conditions here in Rwanda or in Africa that affect me daily in my life, and you are telling me I should be like somebody else. My starting point is to tell you, please put that aside.

Is there democracy without adding the western [to] democracy? If the western democracy works for them, well and good. The other day I was at Harvard [University’s Institute of Politics] and students were grilling me, asking me questions. Then they say, what do you think about Donald Trump? I said, well, what do you think about Trump, because you are the ones who elected him.

Well, I can tell you how maybe the administration and what he does or doesn’t do will affect us, that‘s OK, but to ask me questions to qualify or disqualify this man, I said, I would be assuming too much. This man Trump, he’s a product of your democracy. Sometimes the democracy you tell us to emulate, but you are here complaining about what your democracy gave you.

Nothing is perfect, but I find [here] the principles and ingredients of a democratic society that answers to its people, that allows its people to make choices they want to make, to try and bring people together even with different outlooks, backgrounds, thinking, and work for the common goal. That is development of this Rwanda, this country.

Western democracy answers to certain societies who are coming from a certain place. There are elements, good elements of democracy in what we are doing, but [it] doesn’t immediately fit into the western democracy.

For me to fit into western democracy, western democracy must be fitting into our lives that we have to live as a society maybe with different context and circumstances. So it is a debate that will go on for a long time, but at the same time my viewpoint, at least, is while the debate goes on we must be able to live our lives. We live a life, a real life. It’s not utopian. And I have never come to terms with the idea that somebody else has the right to decide how I live my life, and I don’t think that is part of democracy. Actually, if people believe in values and principles of democracy, I think wanting to dictate the choices and how people live their lives, other people, I think that falls short.

FT: Well, and recent history — for example, Iraq, Afghanistan — is not a happy one in terms of exporting a . . .

PK: Libya. This Libya thing. Syria. You think these countries will be countries again? Not maybe in our lifetime. But these things have happened under the package of wanting to democratise. Colonel Gaddafi was a bad man. I actually had more quarrels with him than anybody.

FT: Is that right? What was your big quarrel about?

PK: It was about him wanting to be seen as the king of Africa and dictating to people and telling people. One time I really lost my cool because of this.

He said, you know, Kagame, you are an agent of western powers, that I am friends with America, I’m friends with the British. I couldn’t help it. I told him, in my personality, in my life, in my upbringing, I would never be anybody’s agent, meaning you are serving somebody else’s interest, you are not serving you. And I said, look back in my history. When I have spent at that time, more than half of my age, I spent it in the trenches. I could not have done that on somebody else’s behalf, never. I said, never, ever, ever point a finger to me and abuse me like that.

It’s like things here must change, this Kagame must go, because that’s what the west is saying. It has come; it’s like, oh, the human rights groups, the champions of democracy of the west are saying . . . the only thing they are saying is, this Kagame hasn’t been doing so badly, but he’s there beyond what we think is the right time for him to stay.

It also reminds me of another conversation. I have many friends in the West. One of them — no, two of them, at different times — they told me, no, but you can do something like has happened in other places; why don’t you groom somebody to take over from you?

Western democracy answers to certain societies who are coming from a certain place. There are elements, good elements of democracy in what we are doing, but [it] doesn’t immediately fit into the western democracy

They went beyond, and they were telling me even some names of our people here. A woman like that, can she be a president? I said, maybe she can. About this, so and so, I said, yes, it’s possible. But then so I turned around and asked him, you’re already suggesting to me those who can actually replace me; that’s fine, so you are determining who replaces me. The other is — it’s really funny — the other is: you are telling me, why don’t you decide who stays in your place so that you remain in control.

Then I said, so there are only these choices you are giving me. You are telling me to go because this is what western democracy wants or thinks, but is that democracy?

Yes, telling me either they choose or I choose. Those are the choices they gave me. They are saying, either you choose who replaces you, or we can choose for you. Then I asked them, I said, there is one constituency you have forgotten. Where are the Rwandan people?

You can see an air of farce about this whole thing, an air of falsehood of . . . let me tell you something else because it applies to me and I think it may be applying to Rwandans: the moment anybody comes to me and thinks he has authority over me and the right to tell me what to do, that’s the time I’m going to do the opposite.

FT: I wonder if we should move to the economy. The question is whether this recent slowdown is a blip, or whether you’ve actually hit a bit of a roadblock and you need to think about the next stage for Rwanda? What lies behind this slowdown?

PK: I think there will always be slowdown, keep coming or maybe going. They do even in stable economies; but we speak about Rwanda — it’s a good question you raised.

We want to invest and keep investing in these ones, and then they form the basis of the sustainability of our economy. One has been: invest and keep investing in our people: education, skills, technology, many things, and then later other things like even in health and so on. We want a healthy population, an educated population, a skilled population, knowledgeable and so on, then technology infrastructure. We are not where we need to be or should be yet, but good progress is part of what you have mentioned.

Second, the private sector: the private sector has been under-developed, too small, the Rwandan private sector, but we have seen growth, very fast growth, actually, the capacity in the private sector for the last, say, 15 years, which has been very helpful. Then we created that business environment for investment, environment for people to come and invest. This has been helpful, for example, the laws that have been put in place, have helped to do that. You’ve seen doing business, the rankings and so on, the efficiencies that we need to put in place for that, to be there when it was not there at all.

Then our economy — two things: how more integrated we are in the region helps our economy. Then there are the externalities, commodity pricing and all that. China, we have seen, of course: if China is in trouble, it affects all of us; particularly Rwanda was affected because we’ve been exporting minerals to China.

Those external factors, the commodity prices and the problems even in the region, much as we are increasing integration programmes in the region, affect us, like in recent days. Even this heading, The Elections Are On, had its own effect. But as you said, thinking of other things that take us to another level, and if you look at the areas of the minerals we have and then others we are finding, we have even come to a point where we say, no, we just don’t need to export minerals as they are; we need to process them. That has already started. It takes a bit of time.

We made a lot of investments also in a number of other things which are going to be better. One simple example is when we set up an airline, the airline consumed resources, but we’re already seeing in one year or so we’ll be in a good position where it is no longer draining a lot of money from us but rather the airline being able to run itself. This is the trend, but we have initially put a lot of money in it. But the airline as such isn’t just a business; we just want to make it a business that doesn’t lose money, and even if it doesn’t make much money, it is serving another purpose. We have seen a continual rise of tourism; tourism revenues have just been increasing, so people are travelling here.

We invested in hotels, people thought we were crazy; why do you pump money into building hotels? We said, because we have opportunity of a growing tourism industry, and when people come here they have to have a place to stay, good places to stay. Same thing — we didn’t have many airlines coming here, and that constrained the ability for people to come to Rwanda for tourism. But now, there are more people coming; so there are more hotels, hotels are filling up, but if we hadn’t triggered this, it would not have happened. It keeps happening like that.

Of course, in-between we continue with the aspect of economic governance as well, make sure we really cut to the minimum the cost of mismanagement. That’s the other area I talked about, about efficiencies; they matter a lot to a small economy like ours, and make sure we don’t lose a lot in corruption and greed, so we keep making sure that what we build are institutions and capacities.

FT: Somebody described it as a calculated risk.

PK: So far it is working. If it doesn’t work, it won’t reach a terrible extent.

FT: It’s not going to bankrupt the country?

PK: Yes, and in any case, I don’t see the alternative.

So we’ve been investing in these things, and I think with more minerals being discovered . . . and, by the way, this is another challenge which we have been discussing among ourselves, when people have said when you find mineral wealth you are just discovering a curse. I’m saying no, my first curse is poverty; and I cannot allow mineral wealth to turn into a problem for me; it’ll just be a solution; it depends on how we manage it. We are really preparing how to do that.

Therefore the next step — again, going back to your question — we want, and we are starting, [is to] build capacity process. We’ve been training people. We are going into areas where we can increase exports; we are going into horticulture; we are now going into manufacturing; we have actually been receiving these small to medium-sized industries that are relocating from China to here.

FT: Mr President, you said something rather interesting a while back, which is that this is a nice problem to have, or we’ve had much bigger problems. You’ve described the success of the Rwandan economy; you’ve talked about your next steps. Clearly, there’s a lot of vitality, and this is serious. Do you worry that some of your neighbours might be thinking, Rwanda’s getting a bit too successful, a bit too big for itself?

PK: I don’t want to sound accusatory, but you know that it happens. It has happened already. But that’s why we concentrate on trying to be as nice with them as we can.

FT: What about the Democratic Republic of Congo? You’re a tiny country next to this huge, potentially incredibly important and vital country, but a mess. And, obviously, there’s a history of things spilling over the borders in either direction.

PK: No, if there was a spillover of people and everything across our border, we would take care of that. I don’t think this would be a disaster. We can manage that. Even if we envision that 2m people can cross — I think that’s putting it too much on the high side — we can still take care of that. And later on, I’m sure others would help. It can’t destabilise us. What is likely to happen in the Congo is an implosion, and Congo has nine neighbours; it will affect all of us. We shall have our own share of the problem. But the only problem I have always been worried about, which has subsided now by far, has always been insecurity that would originate from there affecting us. But we took care of that over the years by building certain capacities.

Long ago, when we used to get war over in Congo, it was compensating for some problem we had. How do I put it? Instead of allowing you to bring the war to me, which destroys everything, I would rather bring the war to you.

FT: Just a quick historical episode, which would be very good if you could address, on the M23 (March 23 rebels] in 2013. There was a lot of talk and also people alleging that Rwanda was “meddling” in eastern Congo. It did some damage to Rwanda’s reputation.

PK: There was, and we had problems and we had . . . we would always blame the British government and those who work for them. There were people blaming the British government for giving us aid. Later on, they even created the story and said, you see, all the aid you give to Rwanda goes to fighting . . . things that are absolutely unrelated and not true.

I remember one time quarrelling with one of the ministers there, who called me on the phone. He said, no, we’re going to cut your aid. I got angry and so I said, you know what, when you withdraw that money, can you please give it to Congo? At least you help the Congolese with that money of ours.

The second thing, for the last 23 years and for all those years were accused of anything in Congo, up to now, I would wish to find somebody who can say, no, you went to Congo because you wanted to exploit resources, the mines, the minerals, and say, this is what you got, this is what you did, this is . . . But they always circumvented the real issue, which we told them right from 1994: the security issues. We would even tell them and say, look, by the way, this is why you put this UN [Monusco] force in; it was actually to deal with the same problems. Tell us what they have done about it.

In the end, it turned out the UN had actually gone there to sit in Congo, and the international community sits back, comfortable that the UN force is taking care of the business, the place is stable for them to go and do whatever they have always done there — never, for once, to address that problem. But we went there, and we always explained. And, in fact, the M23 problem was never our problem.

FT: There’s another story I wanted to ask you about, because it’s a local story but it’s interesting. Is it true that there are three or four genocidaires in the UK?

PK: In a nutshell, just quickly, this case has been going on, I think, for four years now, and there is not a doubt or lack of evidence or anything required to actually, one, prove that these people committed genocide; there are stories here, there are testimonies, there is evidence.

The other thing: we even requested, our government, the first request was that people like this . . . they asked for evidence, their files were sent, everything, because they said, first prove to us that there’s a case. The second was, we were saying, can you give these people to us, because not only are they liable for prosecution, they are actually connected with other cases which have already been prosecuted. I said, so can we have them?

Now, the issue stopped being these genocidaires in the UK and became: should we send them to Rwanda as Rwanda has a working justice system; they’d be treated fairly and so on and so forth, or not. It shifted from this to trying us now, whether we have a justice system to try them or not.

Now, when we saw the complications coming up, all these things, even if I think politics came . . . these human rights, Amnesty International thing, no, you can’t send them to . . . Then we also said, right, fine, don’t send them to us if you don’t want to; maybe we have a bad system; that’s OK. Since you have a good system, can you please prosecute them, just taking the whole thing . . .? Now, these people have actually been released, they have been set free. They dismissed the case.

FT: I heard there had been some DNA testing that throws new interesting light on the Rwandan situation as we tend to understand it, and even on your own position.

PK: OK, I’ll tell you; I have nothing to hide. This man [a professor of microbiology at Stanford University] was telling me details about genomics and the mapping of people and so on, and told me how it is useful and how genetic diseases can be known and maybe avoided in advance. He told me a lot of things about the science, and I got interested.

[An acquaintance] said this science can help us prove or disprove these political theories that have created problems, because the Belgians tried, but they never came with any conclusion, in the 1960s to prove how we are different, here in Rwanda. You probably heard about that.

I said, I don’t mind. And I told him, I said, by the way, I don’t even mind knowing my map of . . . you can go into my DNA and genome and find out what it is. Actually, I took a test and so I know a bit of my own.

We were supposed to do that, take samples from people we think this is one group, this is another, and then do the mapping and see the difference or the commonality. Because we might find the commonality is there, or the difference is just politics or whatever it is. I said, I’m comfortable with that, because in the political discussion here I’d always talked publicly and told people; I said, you see, this is absolutely stupid. Let’s start from the point that we are actually different. I said, so what? Aren’t different people supposed to live together? People will always be different. And, politically, for us, as we are trying to reconcile our society and talk people out of this nonsense of division, I said, so we are different — some are short, others are tall, others are thin, others are stocky, others are . . . I said, but we are all human beings. Can we live together and happily within one border or even one room? What’s the problem?

If we are different, still this difference shouldn’t be a problem; we should turn it into an asset. And if we are the same, then, really, these idiots who come to divide us should know that after all there is no difference. Either way it works.

FT: Does yours tell you anything interesting?

PK: Mine, extremely interesting, because, for example, they found something — in that process, there’s something called hybridisation; that is how many different gene sources combine in you, and they tell me the more you have the healthier the person is.

My gene hybridisation is actually high, higher than normal, the other details, I will spare you.

FT: But does that mean there is some Hutu in you? There must be.

PK: There must be, because looking at that . . . You see, you can’t know. I haven’t known yet which genes belong to the Hutus and which . . . but I can only say why I say there must be, is this diversity in the gene pool . . .

FT: This hybridisation?

PK: Yes. These ones who would divide us and say they are different, they should shut up.

FT: I’m conscious of the time, but tell us about when you decided that English is going to be the official language.

PK: It was a big decision . . . I could see some members of our party and the cabinet doubtful whether we should really do it and whether it was not going to attract a lot of problems maybe that we don’t need. But I insisted with them that, one, from even the actual point of 90 per cent of our trade and interaction and everything, with Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, and so on. And then later on, of course, I was saying, look at the ones who are also giving us aid, above everybody else, and, in fact, for a long time the UK was giving us the biggest chunk of support.

We are trying to reconcile our society and talk people out of this nonsense of division, I said, so we are different — some are short, others are tall, others are thin, others are stocky, others are . . . I said, but we are all human beings

Of course, I had some other ulterior motive in my mind . . . other than the obvious, so there was this obvious one, the practical one; we had so many people who lived in Uganda, in Kenya, in Tanzania, and there were these returnees, probably more than a million, and they all didn’t know French, so they were speaking English. And there are those who lived in the English-speaking part of Europe or lived in Canada or the United States who are coming back. So they didn’t know French, and I don’t think we are going to force them to learn French.

But then the practical thing, really, of business, trade and such things, interactions with east Africa.

I think I even told the French, I said, well, by the way, plus, I think this French rule created these problems for us. If we can get rid of them or minimise their presence here, consider it as one of the driving factors . . . So I told the cabinet, I told everybody, and I’m sure some of them must have told the French.

I said, OK, we will not ban French, but it will stay. So we now have three official languages; now we actually have added a fourth, so it is Kinyarwanda, it’s English, it’s French and Kiswahili.

FT: I’m extremely grateful for the amount of time, so you’ll forgive me — I just want to come back to one last question, the last question. It does come back to this point about leadership, about the question of succession. At some point how are you going to do this?

PK: Overall, one may say it is a complicated thing, but I also think it’s doable; it’s feasible; it’s risky, It’s going to be a matter of process rather than the person, for various reasons, one of them being, if you just pick the person, then that also comes with some dangers. You need to arrive at your person with a certain level of buy-in, buy-in from others.

You don’t need to single out somebody because without knowing, it also creates problems in advance for that person. So you have to be careful. But I think I have a role to play, not in singling out a person and saying, I want this one, but in being part of that process. I can even influence it, there’s no doubt, because at the back of my mind I’m also able to judge.

I will be part of that process, inevitably; there is no point where I think I will switch off and say, no, I don’t care who comes there. No, I can’t, for the obvious reasons. You don’t create problems for somebody who eventually actually may try to or become the leader who comes next, and you want to do it with this buy-in of people, you want to make sure that person also has qualities of really continuing what has been good and what you have built, and maybe do it differently, because it will be a different person. But in the direction that benefits the country and the people.

So there are those criteria one can put in place. It will happen. Because, you see, I’m also realistic too, and I say it again, publicly, even if I was this person who really was dying to be here, to be president and do anything to be here, there is always the reality that point comes, either naturally or otherwise. There is always that point. So I’m not one who will not even think about it. There is no way of avoiding it, but you can avoid leaving behind a mess.